You must go in quest of yourself, and you will find yourself only in the simple and forgotten things. Why not go into the forest for a time, literally? Sometimes a tree tells you more than you can read in books. - Carl Jung

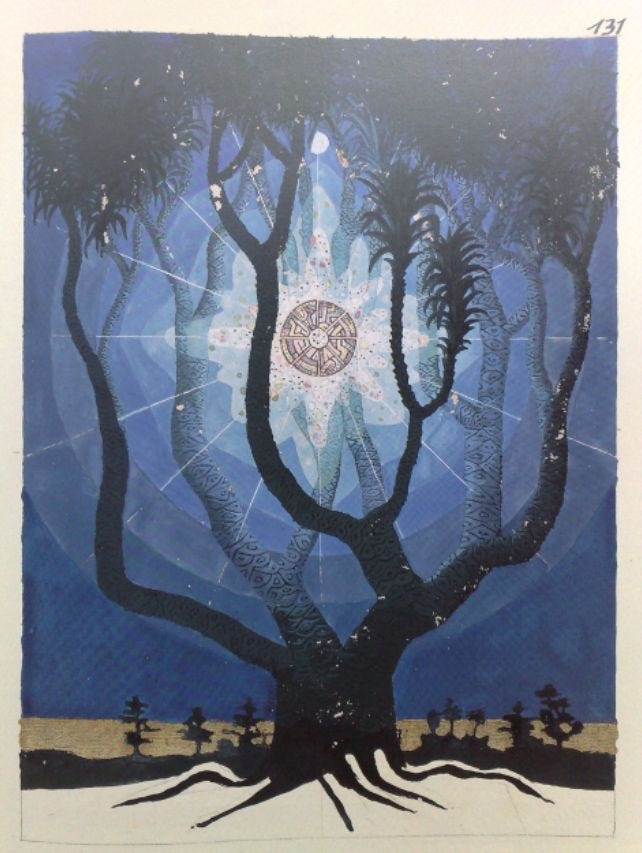

The Cosmos, so say the Icelandic Eddas, is supported by a great tree called Yggdrasil. From this tree, Odin hung for nine days, having sacrificed himself to gain knowledge of the runes. An eagle perches at the top, the beating of whose wings creates the wind, while the dragon Nidhoggr gnaws at the roots. A squirrel, Ratatosk, runs up and down the trunk, sharing insults between the eagle and the dragon. Water drips from the antlers of a stag, browsing the top of the tree with four harts; this water drops into a stream that is the source of all the world's rivers.

This striking vision of the cosmos is echoed in many other world mythologies, but this particular variation expresses something of the Northern psyche: a tad pessimistic, sometimes given to melancholy, but also to an irreverent sense of humour, as the cheeky Ratatosk stirs the pot between the two archetypal forces of order and chaos, the eagle and the dragon. One can imagine him revelling in his role as messenger, chuckling to himself as he scampers along the bark; suppressing his urge to laugh as he watched the dragon and the eagle fume and scoff at one another's taunts.

The great tree Yggdrasil is usually identified as an ash, although there is a compelling theory that this is due to a scholarly misinterpretation, and Yggdrasil was originally conceived as a yew tree. My own suspicion is that this was probably the case, but myths are dynamic, and with so many retellings, the image of the ash as a cosmic tree has already been charged with enough imaginal power to be worth contemplating. Carl Jung's theory of synchronicity, which he termed an 'acausal connecting principle', was simply an elegant reframing of the old principle of correspondence, at least as ancient as human cognition. It is this principle that tells us, much to the spluttering and outrage of the rationalist, that the universe is permeated by a web of integral relationships, so the manifestation of an outward phenomenon in the physical world has the potential to reveal much about what is happening on subtler levels of experience. As such, it is worth taking a look at how ash trees are actually doing in this region of the world, and what this might be able to tell us about how things are going here in the North.

Well, as it happens, ash trees are under quite a bit of pressure right now. A species of fungus, Hymenoscyphus fraxineus or chalara, has spread outwards from the forests of Poland. The fungus causes ash dieback, a disease that is seriously threatening ash populations from Russia all the way over to Ireland. For perspective, I have books from the 1970s that describe Dutch elm disease in the same way that ash dieback is written about now; five decades later, I can probably count the number of fully-grown elm trees I have seen in Britain on one hand. To make matters worse, chalara is not the only invasive species compromising the health of these trees. A species of beetle, the emerald ash borer, is threatening ash trees in North America, and is also spreading outwards from Eastern Europe.

In short, ash trees are diseased because industrial civilization is making them sick. Their immunity will have been weakened by the toxic waste-products of industry, while the movements of global trade will bring them into contact with invasive species they are even less equipped to fend off. This form of civilization originated in the region the ash trees inhabit – the North, the birthplace of the distinct culture that Oswald Spengler dubbed the Faustian. More specifically, industrialization first occurred in England, the same nation in which Rudyard Kipling wrote these lines:

Of all the trees that grow so fair, old England to adorn

Greater are none beneath the sun than Oak, and Ash, and Thorn

The straight-growing ash makes a good spear-shaft; as such, it can be seen as a rather Faustian tree, in light of Spengler's summation of the Faustian ethos as a “straight line extended to infinity”. This Faustian straight line was already in overreach a long, long time ago, and we are now experiencing the blowback; perhaps this is what the sickness of the ash is telling us. We have tried to fashion a spear that could take us to the very edge of infinite space, and the paradox is now manifesting in the health of the very tree that made the spear.

Moreover, the possible misidentification of Yggdrasil as an ash, where originally it may have been a yew, adds another layer to this process of archetypal amplification. If we, as a culture, have burdened the ash with the entire Cosmos, the tree is now straining under the weight. The first man in Norse myth was himself named Ask, 'ash'; the first woman was named Embla, which, curiously enough, has been interpreted as 'elm', although again, this has been disputed. Nonetheless, the traces of synchronicity deserve a brief mention, as the elm began her decline during the 1970s, the decade of faux-liberation sold by the 'sexual revolution'. The ash, on the hand, began to fall ill during the 21st century – as the secular humanist paradigm, which places a genderless 'humanity' at the centre of a disordered cosmos, began to collapse.

[Alexander] then asked the Celts what thing in the world caused them special alarm, expecting that his own great fame had reached the Celts and had penetrated still further, and that they would say that they feared him most of all things. But the answer of the Celts turned out quite contrary to his expectation; for they said they were afraid that the sky would some time or other fall down upon them. Arrian, The Anabasis of Alexander

As above, so below. If the sickness of the ash tree is linked to the existential crisis of meaning afflicting our culture, then can our wounded psyches can be healed with the ash, and vice versa? Experiments with enriched biochar as a soil supplement suggest that it can strengthen ash trees and help them to withstand chalara, while more generally, biodynamic methods show enormous potential in restoring the soil biome to health. Biodynamics, which is a set of agricultural methods drawn from the teachings of esotericist Rudolf Steiner, can be seen as pro-cosmic: the Greek word “cosmos” literally means “that which is beautifully ordered”, and biodynamic preparations are intended to bring the crop back into alignment with that cosmic order. These technologies may prove to be some of the most important developments of the 20th century.

Furthermore, taking the weight of cosmic order from the weary shoulders of our dear old Uncle Ash may be wise. Faustian culture is declining, as Spengler observed a century ago; the time has come to wake up from its fever-dreams of endless expansion and limitless growth, and begin to prepare the ground for what may grow in fecund times to come.

A revolution, in the cosmic sense, is a return to a previous position; it is a process of revolving, rather than revolting. This must be understood as a process of rejuvenation and renewal; the return - or indeed, RETVRN - must also be a rebirth. Such is the wisdom of the yew, who thrusts its branches into the ground to take root and become the stems of new trees, eventually becoming indistinguishable from the old tree. Yew researcher Michael Dunning speaks of this quality of enfolded space as being akin to an embryonic state, and posits the yew as occupying an absolutely central place in indigenous traditions of healing and initiation. Dunning writes:

The earliest known name for the god-like yew tree is the Hittite Eya (1750BCE) which translates as 'eternity,' and by extension, 'to be touched by eternity.' The word taxus for yew is likely derived from the Indo-European 'Tax' which relates to the verb 'to touch.'(6) I was to increasingly experience and understand the 'touch' of the yew as a profound healing force. At first this experience of touch involved a web of gossamer-fine tendrils of light that seemed to originate from the dark periphery of the yew chamber to approach specific 'nodal' points on my skin through which to enter the internal environment of my sick body. I would feel a great pressure build within my body as the light fibres would surround and penetrate an organ, perhaps my liver, and where the liver would then seem to be seized and stretched by these light fibres beyond anything that could be defined anatomically as 'liver'.

Unlike the straight-growing ash, favoured for spears, the flexibility and tensile strength of the yew made it ideal for bows, and this is sadly why so many were felled during the medieval period. European history is characterised by long periods of bloody warfare, and this trauma devastated the yew population. Nonetheless, many ancient yews survived, and they can most often be found in old churchyards, the consecration of which they sometimes predate; the Christian church most probably absorbed elements of the ancient cosmology in which the yew was venerated, as suggested by the fact of a Christian community established out of the old bardic college of Iona, or Ioha – literally, the Isle of the Yews.

The medicinal properties of the yew are slowly being rediscovered. Sadly, this has led to further destruction of the tree, as pharmaceutical companies, hungry for profit, extract the anti-carcinogenic properties of the taxanes produced by the tree. However, this reductive, extractive mindset that damages the ash and the yew, alongside countless other lifeforms, is discarded by the wise. As the sun sets on this phase of our history, and the shadows of uncertainty and hardship loom on the twilit horizon, the sacred yew offers a potent lesson for our future survival: as new trees take root from the trunk of the old, so too must we, as a culture, embrace this process of death and rebirth.

The rediscovery of the medicine of the yew is an opportunity to rediscover a sense of cosmos, a sense of integrity and harmonious order. I believe that the healing of the trees that our ancestors venerated, and the healing of ourselves in the process, is a vitally important aspect of this cosmic restoration. The ash is telling us of our mistake in burdening him with the universe. To restore the yew to its rightful place as the Cosmic Tree, the Yggdrasil, is to restore that which is natural, wholesome, and right; to once again reside sub specie aeternitatis, in the vision of the eternal.

Thanks very much for posting this! I've thought before about how to resolve the ash/yew "contradiction" in conceptualizing of Yggdrasil, but this is an elegant and fruitful take I hadn't considered.

If you haven't seen, Rune Rasmussen has some youtube videos presenting an animist perspective on Yggdrasil that I have found pretty thought-provoking here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=H3onq58Xbpw&list=PLpgfnnXC81dWQ6oHAB3zNFPCJgdVa38Zx and on Ragnarok (including the image of the tree burning), here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Xj0GBGj6QeE&list=PLpgfnnXC81dVjmVIFTXva_PagnXqW9mPN

Cheers,

Jeff

Interestingly, the Kauri in New Zealand, known as kings of the forest, are also suffering from a dieback - though my understanding is that it is the result of damage to the ecosystem of the fungi that its roots rely on.