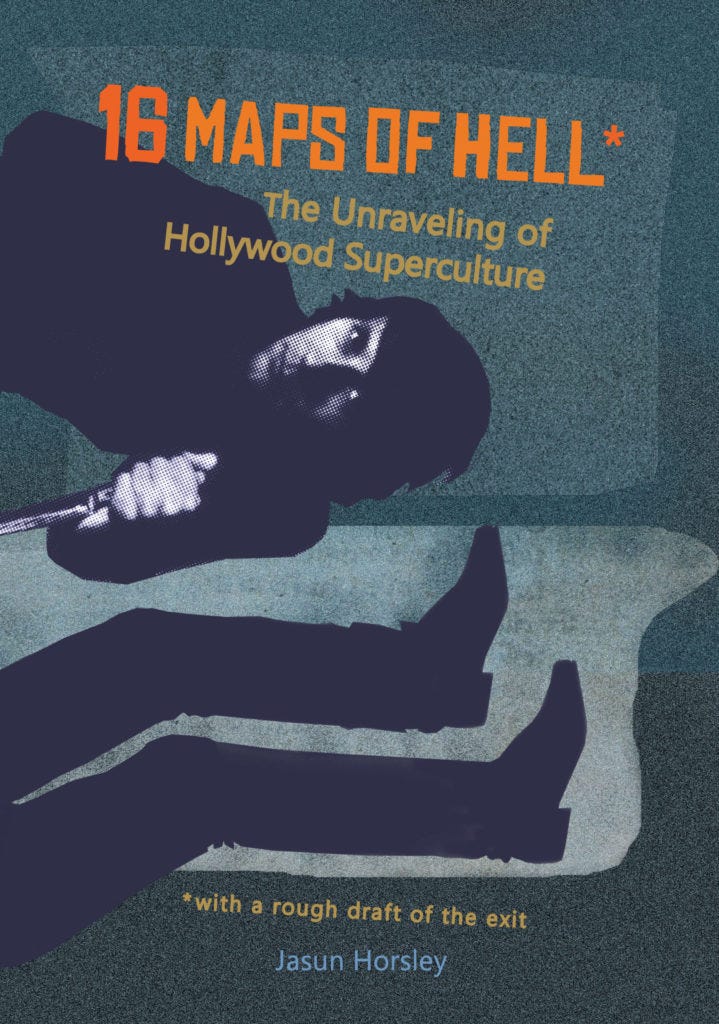

Manifestation of the Anti-Christ: Review of 16 Maps of Hell by Jasun Horsley

This is a companion piece to my latest appearance on the Liminalist podcast.

Electric information environments, being utterly ethereal, foster the illusion of the world as a spiritual substance. It is now a reasonable facsimile of the mystical body, a blatant manifestation of the Anti-Christ. After all, the Prince of the World is a very great electrical engineer.

Marshall McLuhan1

Every day I wake up into a world that looks more and more like an episode of Wallace & Gromit scripted by Philip K. Dick. Dick is quoted as having said: “sometimes the only appropriate response to reality is to go insane”. I have thus far resisted the temptation to take a punt on his advice; going insane in a time like this is to run the risk of having's one's personal madness co-opted into the latest propaganda campaign.

Like the invasion of dreams by advertisers in Futurama, the hijacking of our own unconscious minds by agents of propaganda has been going on for generations. As media technology has become more sophisticated and immersive, the potential of such hijacking has expanded in ways that few among us have even begun to consider. One of those on the vanguard of efforts to decode the propaganda culture is Jasun Horsley, whose latest book 16 Maps of Hell: Unravelling the Hollywood Superculture (*with a rough draft of the exit) applies insights drawn from archaeologist Brian Hayden, anthropologist Gregory Bateson, and philosopher Jacques Ellul to the shadow side of the American film industry. Horsley proposes that:

...as individuals and as a collective, we have been lured – and lured ourselves – into a counterfeit reality, a dream world. Hollywood, as a place and a state of mind, is both a primary causal agency of this condition (over the past century), and a crucial (because visible) symptom of it.

The timing of Horsley's work is interesting, as Hollywood is currently being caught up in the same controlled-demolition that is effecting the rest of the world's economy. The tip-of-the-iceberg revelations of “MeToo” and suchlike had taken their own toll, but box office takings were already in decline before the Coronation of the Virus, and the only reliable earners were increasingly preposterous superhero movies. With the shutdown of public life in effect across large parts of the world, the dark magic of cinema is increasingly being enacted via computer screens rather than movie theatres.

Regardless of how Hollywood is reshaped within the demented cyborg nightmare of the 2020s, in 16 Maps it is treated as a microcosmic reflection of a much broader “superculture”. One literary agent, on being approached with the manuscript, wrote: “I think one would be asking a publisher to bite the hand that feeds them by publishing a book that takes on a system they are invested in”. As a result, the book is an experiment in crowd-funded publishing – each contributor is named personally in the acknowledgements section, so for myself as a contributor, there is more of a sense of direct communication from the author than in anything else I have read.

This makes the stakes appear quite high in terms of reviewing the book. The thesis is not altogether easy to summarise, but here goes: the “hell” or “counterfeit reality” Horsley is mapping, is the ideological matrix constructed by a dark “superculture” with both occult and abusive tendencies. This superculture offers “seemingly “artful” products [that] are merely there to lure us into maintaining our dependency on a system that's designed to sell us endless crap in order to keep on expanding”; the odd bit of anti-consumerist subversion (e.g., Fight Club) is thrown in to placate the counter-cultural types and maintain the pretence of credibility. Hollywood's promotion of consumerism, individualism, and scientism has reached its saturation point in the form of the only gimmick that still reliably works: idiotic superhero films, often saturated with a knowing irony intended to bamboozle the audience into thinking the filmmakers have any respect for their intelligence. Robert Downey Jr's Iron Man, as a cyborg arms dealer who uses his access to high-tech weaponry in order to Fight Evil, has quite naturally become the face of the Marvel Cinematic Universe. The details of how many minerals would need to be plundered, how many labourers exploited, how many chemicals pumped into the environment in the process of creating these high-tech gadgets are left out of the narrative, as irrelevant as the hundreds of civilian lives that would be lost as collateral-damage incurred during the heroes' attempts to save the world.

The implicit neoliberal ideology of superhero films itself conceals an even darker philosophy that Horsley proposes underlies Hollywood: “Torture the women; prolong the dream life; live perpetually ever after”. “Torture the women” was a phrase actually used by Alfred Hitchcock, who enacted it both on- and off-screen. As Horsley demonstrates, Hitchcock was hardly unique as a filmmaker with a streak of sadism and women-hatred. Building on his work in books like Prisoner of Infinity and Vice of Kings, Horsley relates this hatred and abuse of women (as well as children) to the desire to escape the physical reality and create a facsimile in which one has ultimate power; in Horsley's view, this stems from a psyche that has failed to individuate from the mother. This traumatised psyche then seeks revenge on the Great Mother through activities that brutalise the female (and the physical body more broadly) and lead to a dissociation from the realm of matter (derived from the same linguistic root as mother). For Horsley, superhero myths, ego-inflated mystical practices of self-deification, and transhumanism can all be understood as expressions of this pathologically mother-bonded psyche.

Horsley is a writer of blistering honesty, always compelling, often disquieting. In the time I read 16 Maps, while going about my day, I would sometimes feel a background sense of horror and revulsion; the feeling reminded me of the times I have been left profoundly disturbed (even traumatised) by violent media. Leafing through my older brother's copies of film magazine SFX at the age of about 9, I remember seeing a still from the 1995 movie Species, depicting a woman whose spinal column had been ripped out. I was a sensitive child, and even a still image that graphic was enough to throw me off balance for what felt like weeks (time passes slower for children, so it's hard to tell). A few years later, as I progressed through adolescence, my revulsion for violence flipped over into fascination, and I actively sought out the most extreme and disturbing films. Low budget 70s exploitation flicks like Texas Chainsaw Massacre and Cannibal Holocaust, while very distressing, lacked the slickly nauseating quality of more recent Hollywood movies like Se7en or Hannibal. Over the years, filmmakers have been perfecting the art of traumatising their audiences, and the 2018 film Hereditary gets a mention in 16 Maps as a particularly disturbing example of the horror movie “psy-op”, fittingly as the plot of the film actually illustrates many aspects of Horsley's thesis rather well.

The film follows a teenage boy (Peter, portrayed by Alex Wolff) who, in the aftermath of the death of his younger sister Charlie (Milly Shapiro) in a road accident, is subjected to an escalating series of traumatic events coordinated by a diabolist cult in order to prepare the boy for possession by a demonic entity named Paimon. Wolff, in an interview with the appropriately named Vulture magazine, said that director Ari Aster “liked to abuse me, is the main thing”. Wolff goes on to describe how a scene in which he repeatedly bashes his head against a desk was filmed:

I said to him, “Ari, look, if you need to do a real desk, I’ll do it,” and he was like, “I really appreciate that, man.” So we had one that was made out of a sort of soft mat, but under it was hard so it hurt really bad. I remember they brought it in, and I was like, “Shit. This was a bad idea. I wish we’d got a foam one or something that wasn’t that thick.” There was a hardness under it so I was just slamming my face against that thing. But, you know, you’ve gotta do it.

No Kids Were (Permanently) Hurt While Filming Hereditary, Vulture, 2018

The actor goes on to joke that Shapiro “offered to be really decapitated”. When the interviewer asks if Wolff is “in therapy now”, he responds: “Definitely, definitely”.2

When I saw Hereditary in the cinema, I came away feeling that something about the true nature of cinema had been exposed. I was quite shellshocked by the film, and had a few sleepless nights after seeing it; the film's combination of viscerally effective supernatural horror with an acutely empathic portrayal of family bereavement brought up my own experiences following the suicide of my brother Toby in 2011. I had the sense that I had been witness to an actual demonic rite, and had the thought that Peter, whose personality is completely demolished through repeated and horrific brutalisation and who becomes an empty vessel for the demon-king Paimon, represents the audience, who, having been brutalised by watching the film, become vessels for the filmmakers' corrupt ideology.3

This interpretation happens to be very similar to the case that Horsley makes in 16 Maps: that trauma is an essential component in the creation of the “counterfeit reality” of Hollywood. Horlsey quotes Carol J Clover, who writes:

As Marion is to Norman, the audience of Psycho is to Hitchcock; as the audiences of horror film in general are to the directors of those films, female is to male. Hitchcock's 'torture the women' then means, simply, torture the audience.

Consider this alongside the following quote from Jacques Ellul's Propaganda:

An individual can be influenced by forces such as propaganda only when he is cut off from membership in local groups... An individual thus uprooted can only be part of a mass. He is on his own, and individualist thinking asks of him something he has never been required to do before: that he, the individual, become the measure of all things... Thus, here is one of the first conditions for the growth and development of modern propaganda: It emerged in western Europe in the nineteenth century and the first half of the twentieth precisely because that was when society was becoming increasingly individualistic and its organic structures were breaking down.

Just like the Paimon-worshippers of Hereditary require a debased and fragmented psyche to receive their demon-king, so the culture-makers of industrial civilization require a debased and fragmented populace to receive their propaganda campaigns. No surprise, then, that the response to the alleged “pandemic” requires the complete shutdown of public life; the cancelling of all human gatherings; and various absurd mandates that do nothing but lead to the utter dessication of the human spirit.4

On the subject of the so-called pandemic, Matt Hancock claimed that he took inspiration from the 2011 Steven Soderbergh film Contagion for his vaccine policy, another score for Horsley's rather disturbing but highly compelling thesis. Like the strange madness that overtakes the world in Jorge Luis Borges's short story 'Tlon, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius', in which a fictional fantasy world obsesses human society to the point of ousting the real world, our society has become a massive open-air film set, with the quivering masses compliantly taking up their position as extras on the set of a really shit disaster film. Again, the timing of 16 Maps is interesting. As industrial society reveals itself to truly be as hellish as Ellul & co tried to tell us in the last century, the scramble to escape becomes urgent, vital. Cosmopolitan magazine is now openly advocating cannibal fetishism; Teen Vogue are promoting anal sex to a demographic of 11-17 year olds; and Silicon Valley billionaires are harvesting the blood of young people to ward off the aging process. One does not need to be a social conservative to recognise that we are living through a period of cultural decay and indignity that would make the inhabitants of Gomorrah uneasy. Those who may have entertained the idea of getting out of the System and going off-grid before are now getting serious; Jasun is currently in rural Galicia, while I write this paragraph from a village in East Devon.

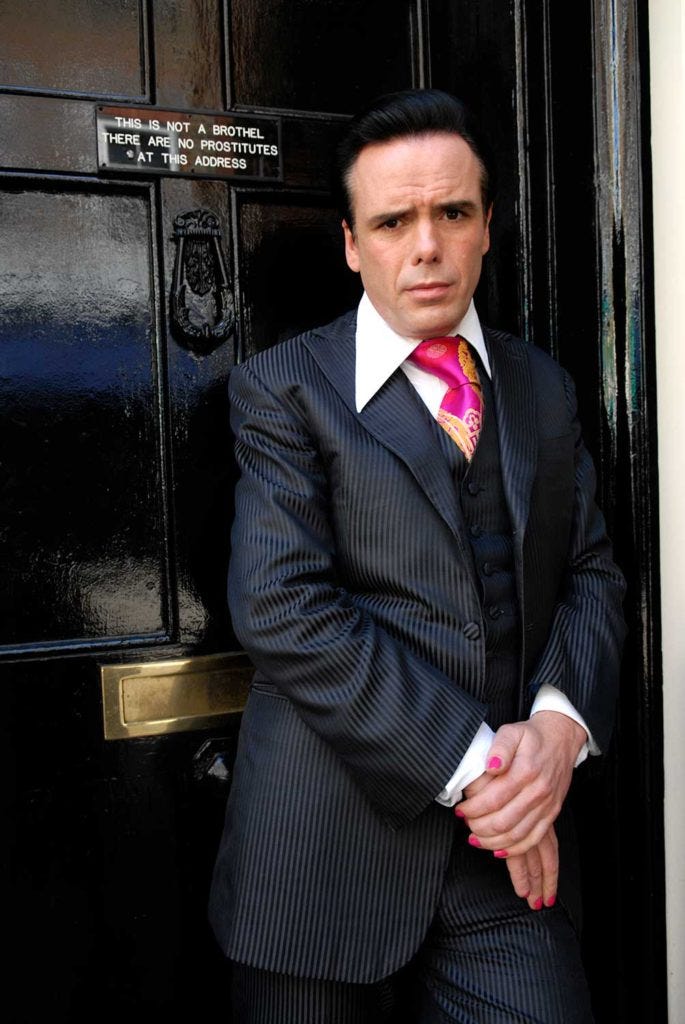

In the background of Jasun's work is his relationship with his brother, the artist Sebastian Horsley, who died of an overdose in 2010. The symmetries between Sebastian and Jasun on the one hand, and my brother Toby and I on the other, were the subject of a conversation we recorded for Jasun's Liminalist podcast last year. Toby, allegedly, idolised Sebastian; they were both dandies, lost in their respective underworlds. Sebastian's death roughly coincided with the first serious breakdown of my brother: severely ill after a yellow fever vaccine, he received the news of the death of his ex-girlfriend Sophie. Presumably, he would have heard about Sebastian's death in this period too. Toby jumped into the river Thames in October 2011; he didn't leave a note.

Sebastian (left); Toby (right)

The connections between our respective lineages don't end there. Jasun's grandfather, Alec Horsley, an industrialist and Fabian Socialist, had collaborated with my great-grandfather, the writer J.B. Priestley, in various British left-wing organisations such as the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, and the Common Wealth Party. Jasun's book Vice of Kings details the dark side of this elite-progressive ideology, symbolised by the Fabian Society's logo of a wolf in sheep's clothing. Priestley's later writings (strongly influenced by Carl Jung) indicate that he may have started to become aware of the wolf-like nature of State-socialism, but the damage was already done – the road towards our current technocratic dystopia had already been laid out, as evidenced by Labour Prime Minister Harold Wilson's 1963 speech on the “white heat” of the “technological revolution”. Priestley also acted as a British delegate to the UNESCO conferences in 1946 and 1947; he would very likely have been at least vaguely aware that UNESCO founder Julian Huxley (brother of Aldous) was a prominent advocate of eugenics, and if he had done a little bit more research, that Huxley's paper UNESCO: Its Purpose and Its Philosophy contained such revealing quotes as

...even though it is quite true that any radical eugenic policy will be for many years politically and psychologically impossible, it will be important for Unesco to see that the eugenic problem is examined with the greatest care, and that the public mind is informed of these issues at stake so that much that now is unthinkable may at least become thinkable.

I will leave the reader to decide how this may relate to present-day public-health mandates; those who wish to investigate further are directed towards the work of James Corbett.5

I cannot blame Priestley for getting involved with these wolves, any more than I can blame him for handing my grandmother Sylvia and great-aunt Barbara over to his second wife, a brutal upper-class woman called Jane Wyndham-Lewis, who cauterised their souls by removing them from their maternal grandmother, their last living link to their mother Pat, who died of cancer when they were infants. Gone were the Yorkshire accents, the elbows perched informally on the dinner table, their happy, carefree lives. Perhaps the fragmentation of the Priestley lineage can be traced back to this trauma, and to the incompetent parenting of Wyndham-Lewis (and, by his chronic absence and womanizing behaviour, Priestley himself). This fragmentation was largely of a more subtle nature than that which affected the Horsley clan – reading Jasun's autobiographical material, I cannot help but be shocked. Certainly, the Horsleys were in the unenviable position of being more deeply immersed in the worlds of business and politics than the Priestleys – the higher up the pyramid, it seems, the more brutal the wolves get.

We have to heal ourselves, and in doing so perhaps we heal our ancestors. When I read 16 Maps, I had a strong sense that my brother was pleased that I had done so. Jasun's writing opens a space for compassion, even for the demons of Hell. Perhaps that's the only way they will lose their power over us.

On my fifteenth birthday – November 16th, 2002 – my brother took me to see Donnie Darko in the cinema. Judging by 16 Maps and its responses, the role that older brothers play in initiating younger male siblings via the consumption of Hollywood movies, popular music, video games, and comic books appears to be quite common. Having been taken into the darkened cave of the movie theatre and drawn into a compelling narrative about a troubled teenage boy who discovers his messianic destiny to rewrite history through an act of self-sacrifice, it might be an understatement to say that the film had quite an impact on my developing psyche. The fact that the film's use of time-travel and parallel universe theory echoes Priestley's “Time plays” (such as An Inspector Calls, We Have Been Here Before, and Time and the Conways) enhanced the film's gravitas by resonating with an ancestral preoccupation.

I identified with the titular character, superbly played by Jake Gyllenhaal, so much so that, in around a year or so after seeing the film, I had spun out my own Darko-inspired inner film-script. In this narrative self-care system, I told myself that a force of spiritual degradation had entered the world around the year 1994, that I was the only one who seemed to be aware of this, and that I needed to perform an act of self-sacrifice (suicide) in order to correct the mistake. I preferred the prospect of suicide-by-live-event, or passive self-sacrifice; the idea of actively taking my own life filled me with dread, and a pre-emptive guilt generated by the nagging doubt that, perhaps, my delusions were just that, and that all I would accomplish by topping myself would be to leave behind a cluster of devastated and traumatised loved ones.

The peculiar knotwork of life arranged itself into a pattern that left me a “survivor”, rather than my brother, as I had long assumed would be more likely. The cultural conditioning that played into our respective delusions is related by Horsley to what he calls “the Thing That Didn't Happen”, inspired by the writings of Joseph Chilton Pearce, who believed that

the human brain is designed to develop in such a way that, during or just after adolescence (i.e., with the awakening of our libido), the frontal lobe becomes fully active and we enter into whole-brain functioning awareness. Spiritually-traditionally, this is called “enlightenment”, the arrival, emergence, or return to no-self selfness, to non-survival-oriented, non-mind-based, holistic consciousness that experiences itself as fully connected to and in harmony with its environment.

Horsley describes the way in which we look to culture as a catalyst for the Thing That Didn't Happen, and this is how we imbue Hollywood movies (or comic book superheroes, or rock stars, etc) with a numinous significance. I suspect that there is a spectrum of Happening/Not Happening on which the Thing can rest, and that the Thing has been Happening less and less the more that invasive technology and social decay has fragmented our lives and psyches. As a consequence, those who were born during the 1980s and afterwards (in other words, who entered adulthood in the age of the internet) appear to be more prone to inane cultural nostalgia than any previous generations – using Nintendo and Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles memorabilia as icons reminding them of when the Future actually seemed like a promising time. Add in narratives that glorify suicide and self-destruction (my brother's favourite singer was Ian Curtis), and the rest is the nightmare of history.

Horsley writes that

Movies (and comic books, and albums and songs, and yes, books about movies) were objects of power animated by adolescent desire. By re-handling them, by turning them over and over in my writer-mind's eye and hand, I am, I think, hoping to regain the power I lost to them.

To finish by returning to the ancestral line, Priestley's Bright Day is by far his best novel in my opinion, and one that even earned the praised of Jung. In this quote, the protagonist, Gregory Dawson, is warned by the artist Jock about the power of projecting one's unconscious contents onto the things that captivate our attention:

Don't turn them, somewhere at the back of your mind, into something they aren't and wouldn't pretend to be. Don't make everything stand or fall by them. Switch off the magic, which comes from you and not from them.

To regain our lost power, to withdraw the magic that we lend to the culture-engineers, is a subtle feat, more akin to pulling a sword from a stone than slaying a dragon. As the System tightens its serpentine grip, however, that sword might become rather useful.

Alison McDowell points out in Dodcast #6 that Michael Bloomberg began his career as an electrical engineer, and that Bloomberg's London office is built directly on the site of the Temple of Mithras. None of this is intended to suggest that Bloomberg is necessarily the Antichrist, of course.

In the US, trailers for Hereditary were shown before screenings of Winnie the Pooh; officially, this was a "mistake", but Horsley suggests malicious intent. When I saw the film, a group of children had inexplicably been let in; they were acting up and obviously disturbed by the film, whereupon their parent/guardian told them to "sit down"

The film's last scene shows Peter, now fully possessed by Paimon, gazing vacantly at the camera; the music playing over the end credits is Judy Collins's “Both Sides Now”, an insipidly happy bit of 60s folk-pop which, in context, becomes outrageously mocking. If the filmmakers had chosen to continue using Colin Stetson's weird saxophone noises instead, it would be more appropriate. The inappropriate choice of music seem like a final taunt – as in, the bad guys won, and the filmmakers are going to celebrate that fact.

As Paimon in real-life occult grimoires is depicted with a crown, Hereditary's final scene shows the severed head of Charlie adorned with a crown – or in Latin, a corona. Synchro-mystics, take it from here.