I was recently reminded of the paper that I delivered at Breaking Convention 2015, by one of those emails that Academia.edu send out to cajole you into signing up for their premium service:

Congratulations on your 5th Mention! View your mentions with 50% off Academia Premium when you upgrade in the next 2 days

Having been out of the academic loop for a little while, I'm not entirely sure when a “citation” became a “mention”, but I imagine it was around the time “programs” became “apps”, “sex” became “gender”, and “experimental gene treatments” became “safe and effective vaccines”. In any case, the success of their attempts to play on our vanity is contingent on the ability to run a basic Google search for one's own name, so I don't know how well it works on most people. As it turns out, my 5th Mention! was in an unusually interesting academic paper entitled What Most People Would Call Evil: The Archontic Spirituality of William S. Burroughs, published in the religious/esoteric studies journal La Rosa di Paracelso in 2018. In this article, Cowan makes reference to a paper I delivered at Breaking Convention in 2015 entitled 'The Real Secret of Magic: Burroughs, McKenna, and the Syntactical Nature of Reality', which was itself adapted from the MA dissertation I submitted to the University of Kent in 2012, entitled Rewriting God's Script.

Cowan's charitable view is that my thoughts “regarding the lineage of New Age Mayanism, though cogent, are addressed in the superficial fashion necessitated by the limits of a conference panel”. I would go further than him, and say that the superficiality of my thoughts was not just an artefact of limited time, but the narrowness of my thinking as a fully paid-up member of the counter-culture, and an aspiring member of the counter-cultural elite. Cowan himself touches on some of the deeper issues regarding the occultic dimensions of Burroughs's writing, and by extension Terence McKenna's and all of those others who have followed:

Burroughs’ themes through which he explores the body (drugs, violence, sex) can read like a critique of the body, things of the world which help to make us keep ourselves imprisoned through our desires. Yet, there is another dual meaning here: the archontic weapons used against humans, (i.e. these bodily restrictions through which we imprison ourselves), can also be inverted, can be weaponized in other ways and transformed into instruments that allow us to escape the body. To give an example, Burroughs often thought that the biological need for sex was one of the most powerful vices that kept spirits trapped in the human body; this negative view of sex could be influenced by his childhood experiences with sexual abuse.(emphasis added) However, sex magic, frequently depicted as the “flash bulb of orgasm” in The Soft Machine, is one of the most common ways in which Burroughs’ characters escape their bodies. Therefore, sex, drugs, and violence are ironically also tools of transcendence, and within Burroughs the line between bodily imprisonment and liberation is frequently obfuscated, the negative and positive connotations rapidly vacillating, or even coinciding. (emphasis added)

Cowan has to leave this crucial point hanging, as it is tangential to the overall point of thesis, which is a very articulate defence of the academic value of esotericism against the sneering disdain of critics like Duncan Fallowell, who dismisses the topic as having “no autonomous academic worth” in his review of Barry Miles's Call Me Burroughs, published in The Spectator. This is exactly the kind of dreary attitude that inspired me to write my Masters thesis; emerging from the pleasant haze of undergraduate study into the harsh light of postgraduate, I found my growing interest in religious experience was met with more or less open hostility by some within my department, a hostility that seemed all the more outrageous knowing of my brother's hash-induced mystical trip that ultimately sent him over the threshold of sanity and into the watery embrace of the river Thames. Failure to integrate spiritual experience could literally be a matter of life and death, so the smug faux-intellectualism of people like Fallowell formed a useful thrust-block against which to articulate my own ideas, as it evidently has for Cowan as well.

However, having been outside of the academy for many years, and having undergone my own process of reevaluating the counter-culture with which I identified so deeply in my early- to mid-twenties, defending esoteric and occult practice as worthy of academic study does not have the same urgency, particularly in cases like Burroughs's, which raise much deeper questions about what kind of occult practice we are talking about, and whether it is actually worth defending in the first place.

In other words, to really get to the substance of Burroughs's dabbling in the occult, we have to take it on its own terms as the attempt of a traumatised and fragmented human being to achieve psycho-spiritual integration. Viewed in this light, it can only be seen as a spectacular failure. Having killed his wife Joan Vollmer in a bizarre stunt that stands somewhere between accident, murder, and assisted suicide, Burroughs subsequently spent his life shooting heroin, writing weird books, and sexually exploiting underage boys. His son, Billy Burroughs Jr, died at the age of 33 after he stopped taking his medication; his alcoholism and drug abuse had left him with a liver transplant. He had cut off all contact with his father, and claimed that his father's friends had abused him in Tangiers.

Which brings us back to Cowan's point that “within Burroughs the line between bodily imprisonment and liberation is frequently obfuscated”, which is something of an understatement, and one which obscures a degree of psychological nuance. Burroughs's obsession with escaping the body arose from the trauma stored within his body; his efforts to achieve this through dissociative practices (such as heroin, pederasty, and garbled occultism) only served to enhance his psychic fragmentation, leaving the trauma within his body unhealed. If, for Burroughs, the line between bodily imprisonment and liberation was often unclear, this is because the two concepts are co-emergent properties of the same underlying desire to heal. As is so often the case with severe trauma, however, this desire to heal was corrupted and overridden by Burroughs's pathology.

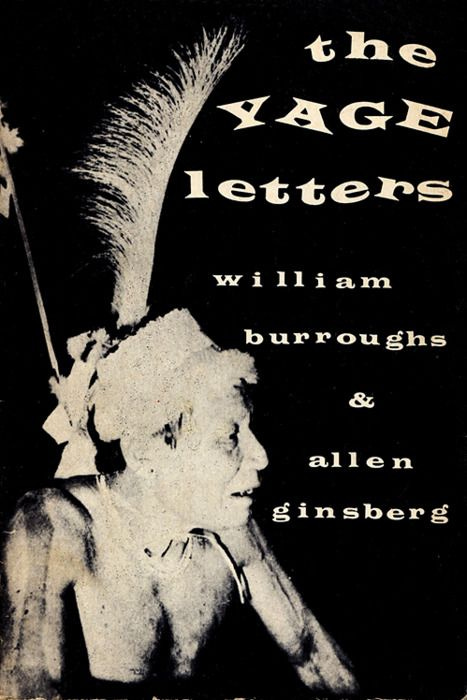

Shortly after he shot his wife, Burroughs became one of the first 'ayahuasca tourists', his travels documented in The Yage Letters. Convinced (probably with good reason) that he shot his wife in an episode of spirit possession, he became a trailblazer for thousands of psychonautic seekers, flying out to South America in search of a curandero. However, while his ayahuasca experiments provided him with inspiration for his depiction of the city of Interzone in Naked Lunch (some of which is repeated verbatim from his 'trip report' in The Yage Letters), they evidently did very little to help him confront his trauma, and he remained a junky, on and off, for most of his life thereafter.

What does this say about the counter-culture which idolizes the likes of Burroughs? As he was invited by Bill Clinton to give a poetry reading at the White House in 1993, it is debatable whether Burroughs was a member of the counter-cultural elite, or simply the cultural elite, and what would be the difference between the two (Burroughs ignored the invite, according to witness Al Jourgensen, because he was too busy shooting up heroin). It can seem harmless enough to celebrate Burroughs's writing; some are drawn by his status as a 'queer', 'postmodern', or 'transgressive' writer; for others, such as Cowan and the 24-year old version of me, his disorganised spirituality forms the locus of appeal. But in the 21st century, when the existence of organised child abuse within the upper echelons of media, government, and finance has become impossible to deny without using obfuscation and hand-waving, and the possibility that this organised abuse may in some cases have a ritualistic or 'occult' nature cannot be decisively ruled out, looking at a case like that of Burroughs with no more than a cursory nod to the key issue of trauma seems evasive at best.

When I wrote Rewriting God's Script at the age of 24, I neglected to even mention a rather disturbing detail in my discussion of 'The Mayan Caper', the first chapter of The Soft Machine: the “vessel” which the narrator uses for time travel is the body of a psychically gifted 20 year old Mayan worker. The description of the surgical transfer of the narrator's consciousness into the unfortunate young Mayan is difficult to decipher, but in typical Burroughsian fashion, appears to involve the narrator “vomiting and ejaculating in the Mayan vessel”. After more ejaculation and suchlike, the narrator's consciousness is transferred into the “vessel”, and this leads to him travelling back in time to the height of the Mayan empire, for some reason. The time-travelling conquistador-narrator then liberates the subjects of the empire from the demonic Mayan control-system by tricking one of the shapeshifting crab-men that make up the Mayan priesthood into having sex with him, whereupon he uses his “camera-gun” to capture some footage that allows him to perform cut-up magic on the crab-priests and bring down the Mayan empire: “Tidal waves rolled over the Mayan control calendar”.

The reason I neglected to mention the hideous sexual exploitation of a young impoverished Mayan man, or most of the other repugnant details of this piece, in my Masters thesis was that I understandably found these details distasteful, and would not have been able to adequately deal with them without taking a much more sceptical stance towards the trauma-generated metaphysics that permeates Burroughs's work (and life). The extent of this denial led me to describe Burroughs as a “moral writer” in a talk given at the University of Kent in 2016, which my friend and dissertation tutor Will Rowlandson quite rightly challenged, stating that Burroughs's writing is profoundly amoral. Cowan points out that Burroughs's metaphysics often get overlooked by literary critics who are more interested in his transgressive amorality, “as if his unique spiritual views were but subcomponents to an antinomianism more essential than the metaphysics that antinomianism creates.” I would suggest that, in fact, the postmodern literary critics to which Cowan refers are not entirely unjustified in this; Burroughs's antinomian metaphysics were as incoherent as his literary cut-ups, and his esoteric practice can only be viewed as incompetent, if it was intended to achieve anything more profound than hexing the odd London cafe.

However, while a new wave of religious studies scholars following Jeffrey Kripal1 are ostensibly taking the spirituality of “weird” American writers like Burroughs more seriously, the issue of trauma, and the inextricably related issue of social engineering, are dealt with by these scholars in a manner that is often cursory and superficial at best, if at all. Jasun Horsley, in Prisoner of Infinity, describes his clash with Kripal over the nature of trauma-generated spiritual experience, with Kripal maintaining that there was no essential difference between an authentic spiritual enlightenment and a trauma-generated psychic episode, and that Horsley's concern that “trauma-induced spirituality would be informed by the trauma, in other words, that it would be compensatory”2 was therefore unfounded. The possibility that there might be a difference between compensatory and revelatory spirituality is not on Kripal's agenda; by collapsing the distinction between the two, Kripal engages in a kind of reductionism far more insidious than that of someone like Fallowell. Whether this stems from Kripal's naivete, or an unwillingness to admit that there is a very dark side to the postmodern esotericism for which Kripal &co have become the academic torch-bearers, is unclear.

“Where Eros cannot go, Thanatos reigns supreme” is a concise summation of Horsley's thesis, that when life-force (eros) is interrupted by trauma, libidinal energy manifests in pathological ways; in other words, directed towards death (thanatos), rather than life. One can see the conflation of the two in the name of the Illuminates of Thanateros, an occult group into which Burroughs was initiated. The IoT's theories of 'chaos-magic' have become relatively mainstream via the likes of Grant Morrison and Genesis P Orridge, and even entered the lexicon of the fashion industry in 2015; I got a tattoo of an eight-pointed 'chaos star' (a design originally from the fantasy novels of Michael Moorcock, incorporated into the symbolism of the IoT) in 2010, during my own phase of dabbling with 'sigils' and suchlike. Alongside Burroughs, another key influence on chaos-magic is the writer Hakim Bey, AKA Peter Lamborn Wilson. Wilson, who popularised the concept of the 'Temporary Autonomous Zone' which most recently surfaced in the 'CHAZ' street-theatre psy-op of 2020, describes himself as an 'ontological anarchist', and shared a house with Burroughs in New York in the late 1970s. Wilson has also written pieces for paedophile advocacy group NAMBLA, that include graphic descriptions of child abuse; his druggy, utopian, far-out-man prose conceals a philosophy as depraved and brutal as that of Burroughs, without the Swiftian humour and biting cynicism that gives Burroughs's writing its unique appeal. He also provided Burroughs with historically questionable material related to Assassin leader Hassan-i-Sabbah, to whom is attributed the quote “nothing is true, everything is permitted”; given that he had his own son put to death for drinking alcohol, Sabbah is very unlikely to have actually said anything like this, but it has become a popular aphorism amongst chaos-magicians, Thelemites, and other antinomian occultists with a postmodernist bent. Much like Crowley's “do what thou wilt” (originally taken from Rabelais), it can be interpreted in various different ways, but provides ample justification for all sorts of deviant behaviour.

This gets to the crux of my issue with the way people like Burroughs are dealt with by critics; their 'liberatory' ethos becomes another form of imprisonment, because it perpetuates trauma, rather than overcomes it. Experiences of bodily violation, of the type described in Burroughs's writing (both autobiographical and fictional), can be reframed using 'antinomian metaphysics' as being part of a spiritual process of self-development. The trauma passes on through abuse and neglect and the cycle continues anew, until the pain is healed, or (as with Burroughs Jr), the subject simply self-destructs.

Looking at the society in which we now find ourselves, in which artificial intelligence guides our daily decision-making processes, and technology has provided a system of global manipulation the ancient Mayans would not have been able to imagine, I can see Burroughs the culture-maker as having inadvertently played his own part in creating it. The nuance and paradox of this suggestion is very much evident in Burroughsian cultural artefacts such as The Matrix. Cowan writes:

One framework through which the secularization of archontic agency operates in the Matrix films is Lewis Mumford’s “myth of the machine”: a notion common to modernity that granting high authority to science will translate into the best societal results because science allows for greater economic control.

The fact that Cowan is able to apply the ideas of a sophisticated critic of technology like Mumford to a Hollywood franchise like The Matrix is testament to the power of the machine to reveal its own nature, and sell a simulation of rebellion in doing so. The apparently Gnostic and Luddite themes of the original movie have been revealed by the directors as – quelle surprise! - an allegorical rendition of why invasive and irreversible surgical and pharmaceutical interventions in the human body are completely justified by an incoherent gender ideology, in which the ephemeral whims of the traumatised mind take precedence over the integrity of the body itself.1 The original film ended with a song entitled “Wake Up” by corporate-leftist rockers Rage Against the Machine, a band that have since come out in favour of vaccine mandates. Android wolves masquerade as electric sheep, once again.

Looking at footage of Burroughs now, more than anything else, I see sadness in his eyes. A vulnerable old man, scion of a wealthy family, nephew of Ivy Lee, whose work pioneered modern public relations, and whose clients included Nazi Germany. What I always found fascinating about his writing was his dark, abrasive vision of 'Control', and how it revealed such insight into the nature of the society that Burroughs's own family had helped to create. Returning to his work now, I see the pathos in his eyes as resulting from the fact that his frantic efforts to free himself from what he called the forces of 'Control' led him further into its clutches.

Such as Cowan, Erik Davis, and Diana Pasulka.

(2013: 5)