The world is charged with the grandeur of God.

It will flame out, like shining from shook foil;

It gathers to a greatness, like the ooze of oil

Crushed. Why do men then now not reck his rod?

Generations have trod, have trod, have trod;

And all is seared with trade; bleared, smeared with toil;

And wears man's smudge and shares man's smell: the soil

Is bare now, nor can foot feel, being shod. - Gerard Manley Hopkins

For all that I bemoan the decline of England, there are some very significant ways in which we have brought our misfortune upon our own heads. As second- and third-order consequences practically rain down from the skies – or, indeed, arrive by dinghy from across the Channel – it is worth taking stock of our own history to understand where we might have take a little bit of a wrong turning, and perhaps more importantly, where contemporary narratives might be hindering us from redressing our course.

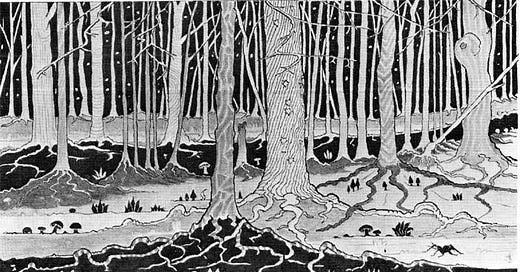

A beautiful example of both can be found in a very interesting Xitter thread by Sam Bidwell, who is Director of something called the Next Generation Centre at the Adam Smith Institute, the “#1 Economics Think Tank” devoted to “[promoting] markets, liberty, innovation, progress & growth”, according to their X profile. Bidwell's thread is a clear, well-written, and informative thread on how the English landscape has been shaped by economic imperatives from the forest clearances of the Neolithic up to the Enclosures of the 1700s. Bidwell describes how England's vast stretches of wetlands were drained to become productive agricultural land, and how temperate rainforests teaming with brown bears, wolves, wild boar, bandits, and dissidents were cleared to open up trading routes between major urban centres. It is hard not to project a note of grief and loss into Bidwell's description of how the wild boar was hunted to extinction in the 1700s,1 or how England's denuded countryside compares with the more densely forested regions of continental Europe. However, such biophiliac tendencies are totally absent, and to my astonishment, Bidwell concludes his thread triumphantly:

I suppose, for those of a Whiggish persuasion, the Enclosures – the name given to the process whereby wealthy landowners sliced up the common land of England and sold it off, impoverishing the peasantry and leading to the total abandonment of hundreds of villages across the land – might seem like a “true feat of national competence.” I suppose the elimination of England's temperate rainforests along with hundreds of species of wildlife probably seems like a necessary step towards making London the centre of the world's financial markets. Who the bloody hell would invest in a swamp, anyway? Unless you're investing in 'natural capital', of course.

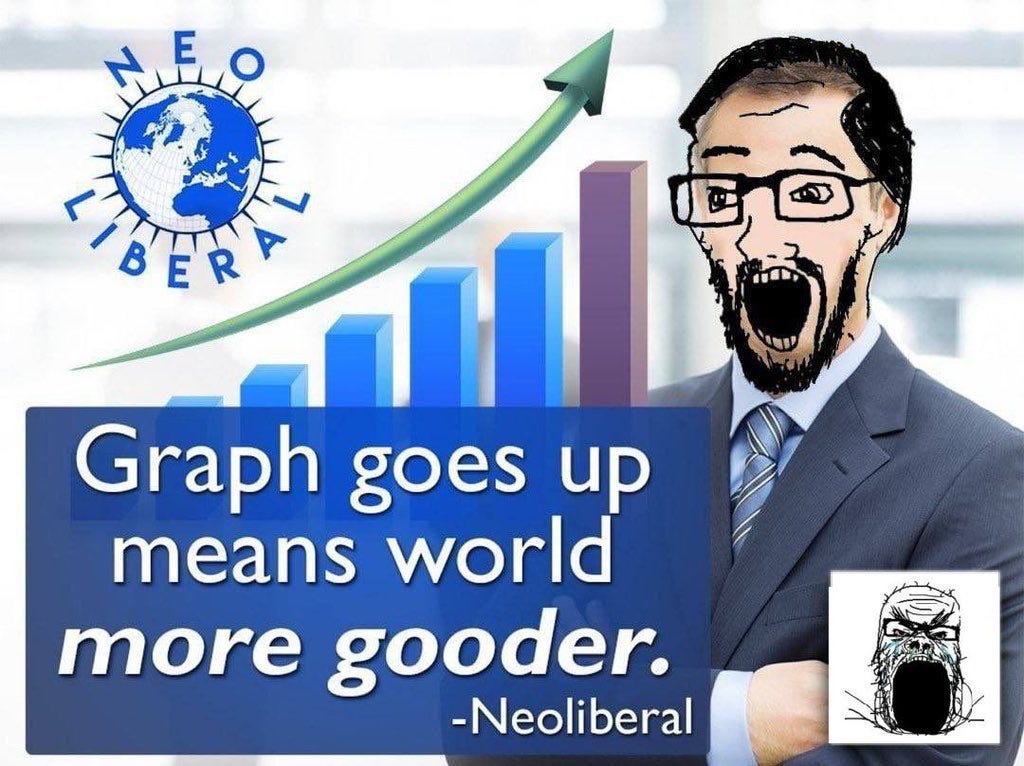

Which brings me to the irony that the spreadsheet-brained usually miss. While they offer milktoast criticisms of Davos globalism from an old-school Thatcherite perspective, what they don't realise is that their own ideology is simply an obsolete form of proto-globalism that was discarded by most of the elites by the 1990s. For all that they protest the 'green' policies pushed by George Monbiot, Bill Gates, and the like, these policies are just a rebranded version of the Enclosures that Bidwell celebrates as a “national achievement.” The “New Deal for Nature”, a plot to carve up half of the Earth's surface and set it aside in the name of 'sustainable rewilded carbon sequestration' or some such bullshit, is really the logical end result of the Enclosures. The “Great Reset” is a land-grab. Eat the bugs and live in the pod, because the guy on the TV told you to. The countryside isn't for you, citizen, unless you've earned enough social-credits to spend an extra day or two hiking in the Protected Nature Zones.

Bidwell is correct that this process was spearheaded by the English, or at least, by the rich landowning segment of the English. The demise of feudalism – in which enough noblesse oblige was expected of the aristocracy that they would sometimes be required to act on it – led to the development of a mercantile society to which much of the English aristocracy adapted fairly quickly. It wasn't just in England, either – the Lairds of Scotland betrayed the people of their own clans by clearing out the subsistence farmers to make way for profitable sheep-farming. The Highland Clearances, as they came to be known, were the final nail in the pinewood coffin for what remained of the Caledonian Forest, as native land-management gave way to overgrazing by sheep and a rampantly uncontrolled deer population.

Friedrich Nietzsche engages in some entertainingly vitriolic rants about the English in Beyond Good and Evil; he lambasts us as an “unphilosophical race'” engaged in the “mechanical stultification of the world”, and comments:

That which offends even in the humanest Englishman is his lack of music, to speak figuratively (and also literally): he has neither rhythm nor dance in the movements of his soul and body; indeed, not even the desire for rhythm and dance, for "music."

Unfair and overstated, perhaps, but that was Nietzsche's style; expecting English understatement from him would simply prove his point. Not quite as effectively as the Adam Smith Institute, however, as modern-day inheritors of the “attack on the philosophical spirit” represented by the likes of Francis Bacon. The dreary “graph go up means world more gooder!” mentality is shared by liberals of both the 'classical' and 'neo' varieties, a deadened world of 'progress and prosperity' in which nature, music, art, philosophy, mystery, and the essential animating force of life are seen as commodities, where they are even recognised at all.

Even a Martian Wyrdlord like Carter and a tree-hugging wannabe Druid like myself can agree on this point. I appreciate the beauty of England's landscape, and the complex interplay of human and natural forces that have alternately clashed and conspired to make it what it is. But when the land is deforested, drained, and domesticated, when the apex predators are killed off, and when the people who relied upon it for generations are dispossessed, something is lost, something that is far more than the sum of its parts.

And when that is lost, there is no longer any break on the hubris of man. We English eradicated our main mammalian rivals, the brown bear and the wolf, in the Middle Ages; drunk and swaggering in our victory, we then created a system that denies all values beyond those which could be reduced to economic imperatives, and set about exporting it to the rest of the world, without pausing to ask if it was really benefitting us, let alone anyone else. Our island became known as 'perfidious Albion', and not without good reason. These domesticated chickens have come home to roost, and the end result was globalism. The vision of the human as a mere machine of economic productivity has real-world consequences, as Mary Harrington's recently unpaywalled (and highly recommended) series on the work of Renaud Camus shows.

Rudyard Kipling wrote, “Of all the trees that grow so fair, old England to adorn / Greater are none beneath the sun, than oak and ash and thorn.” Well, thanks to the industriousness of the English in promoting global trade and innovation and all the other things that boring think-tanks are into, those trees are growing sick; the oak, symbol of English steadfastness, is threatened by multiple disease including Acute Oak Decline and Chronic Oak Decline (both highly symbolic), while the long-term survival of the ash is in question due to the notorious ash dieback. As I suggested in The Trees that Hold the Cosmos Together, perhaps our trees becoming ill can tell us something about what is happening at a human level. Perhaps, by remedying the blight on our trees, we can begin to reverse the blight in our culture.

The Trees that Hold the Cosmos Together

You must go in quest of yourself, and you will find yourself only in the simple and forgotten things. Why not go into the forest for a time, literally? Sometimes a tree tells you more than you can read in books. - Carl Jung

Bidwell neglects to mention that wild boar is one of the tastiest things on Earth. Such is the demand for its meat, in fact, that boar have been accidentally reintroduced over the past 50 years, as captive animals have escaped from farms and back into the wild. For those who find the idea of such dangerous wildlife to be intolerably frightening, I’d recommend that you avoid spending any time in the Forest of Dean, which has one of the largest populations of feral boar in the country.

As a wannabe druid myself, I find great comfort in the presence of ancient trees. The UK is very competent indeed at trashing everything natural, wholesome and good for the spirit.

Bring back scary forests where myths and legends abound, filled with a myriad of different creatures, seen and unseen.

There is unrest in the forest

There is trouble with the trees

For the Maples want more sunlight

And the Oaks ignore their pleas

At the end of the song, with great irony

The trees are all kept equal

By hatchet

Axe

And saw

In my state of Michigan our illustrious betters have concluded they need 215,000 acres to be cleared for the Green New Deal windmills. With great irony we will lose ecosystem, because the spreadsheet peeps and technocrat rockstars are so disconnected from Nature they believe their models and other abstractions will save Nature. It’s frightening.